In the microworld, even apparently ugly things can be beautiful

He studied molecular biology at the Faculty of Science of the Charles University. Soon after graduation, he joined our faculty, in particular the Institute of Pathological Physiology, where he focuses among other things on blood-forming stem cells and cellular hypoxia. Nowadays, he does not do much experimental work but his interest in experimental animals did not wane. He is in charge of the faculty’s animal facility. At the same time, he united his interest in science and nature with his love of photography, and he did that most successfully. His scientific microphotography, which he creates using the electron scanning microscope, nowadays travels with international exhibitions around the globe. For the First Faculty of Medicine, he created already the second charity calendar whose aim is to support non-profit organisations. He admits he does not like having pictures of himself taken and that for a long time, he did not like the transition to digital photography. Mgr. Viktor Sýkora, head of the Centre for Experimental Biomodels.

What does your centre provide?

We are a service institution, so our mission is to provide access to laboratory animals to researchers from the faculty but also other institutions. We provide mainly mice and rats, and to a smaller extent also rabbits. We have to take care of them, make sure they are healthy, have the right temperature and humidity in their cages, good food, enough water, and such like. This is linked to administrative work including all the requisite permits and administration of experiment designs, which have to get a permission from the Ministry for Environment to go ahead. We receive accreditation by the Ministry of Agriculture, but when it comes to genetically modified organisms, we have to communicate with the Ministry of Environment, while certifications for proper laboratory practices are prepared in collaboration with the State Institute for Drug Control. We also receive visits from the State Institute for Nuclear Safety, State Veterinary Administration of the Czech Republic, Czech Environmental Inspectorate, etc. We really live under a microscope and must make sure to have all the right papers for all these institutions.

Photo: Markéta Sýkorová

How do you manage all this administration?

It is difficult but I cannot let it defeat me. I must keep my head up, deal with it, and behave correctly. Throughout my entire time with the institute, we had no negative feedback from any of the abovementioned institutions. For far, we are actually doing really well, but we must keep track of the changing legislation, including for instance the size of animal cages or containers.

Where do you get the animals from?

Some genetically modified animal breeds are commercially available and one can simply order them – of course with the requisite administration that includes standards of veterinary care during transport. In most cases, we buy a small group of animals whom we breed to have enough for a particular experiment. This is because one transgenic mouse can cost up to 10,000 CZK. But just for comparison, even a ‘common’ laboratory mouse, which is not genetically modified, is not cheap: it costs around 600 CZK. So, when a larger number is needed, it pays to breed them. Other types of experimental animals come to us mostly via various research teams who established collaboration with the relevant institutions in the Czech Republic or in fact anywhere in the world where the requisite strain has been developed.

In your animal facility, the environment must be quite friendly to make the mice want to breed ...

Certainly. Animals live in strictly controlled conditions and any manipulation with them must be authorised. For instance, temperature must not deviate by more than two degrees from the prescribed norm, and if it changes, we must within 24 hours make sure that it gets back to normal. If we compare it to conditions for patients in hospitals, where some still do not have air-conditioning and in the summer, the temperatures in hospital rooms can be really high, the mice and rats are having a great time.

In society, the keeping and breeding of laboratory animals is still a controversial topic. Do you ever have to defend your work?

Not really at the faculty, because there everyone basically understands that without pre-clinical research on animals, we could not move medicine ahead. Someone once actually took the time and took all Nobel prizes in medicine which had been awarded so far, and found out that save for two exceptions, they were all to some extent based on experimental biomodels. That says it all. Especially nowadays, with respect to developing new drugs, one cannot do clinical testing without preclinical testing on animals. Alternatively, someone would have to propose that we should try all drugs straightaway on people, but I do not think anyone would seriously consider that.

Another argument is that the number of experimental biomodels represents only a tiny fraction of the percentage of animals we kill for fur, meat, or simply because we find them inconvenient. For instance, the capital city of Prague pours into its sewers some 3,000 kg of poisoned granules each year, and these kill rats in a rather nasty way. Laboratory animals, on the other hand, may be killed only in a prescribed humane way, for instance by anaesthetic overdose. A rational person will thus understand that there are some much more problematic areas of human’s relation to animals than those represented by biomodels.

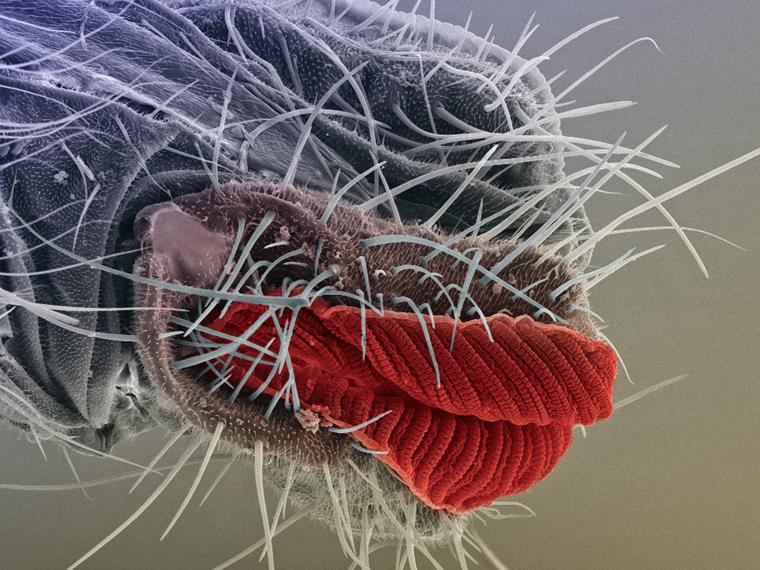

Kiss, please! With this image of fly proboscis,

Viktor Sýkora won this year’s first place in category Humour in Science at the

Art in Science competition in Copenhagen. Photo:

Viktor Sýkora

What do you enjoy about your work the most?

I like the fact that it gives me the opportunity to look into various projects and from time to time, I can be involved in them. In this way, I try not to lose touch with the experimental part of biomedicine. At the moment, I am interested especially in tracking stem cells using a mouse model, that is, in tracking of how cells move in an organism and what happens to them using various imaging methods.

At the First Faculty of Medicine, you are also known as a photographer and in the past two years, you have created the faculty’s charity calendars. For how long has photography been your hobby?

Since elementary school, when I got the first camera in my hand and for about two years, I attended courses at the People’s Art School. I was a classical amateur photographer who takes pictures of whatever he likes: street life, architecture, nature... When I started studying at the faculty, I neglected photography a bit but after 2000, we founded with colleagues a photo club called ‘The Thirteenth Chamber’. I started taking pictures more often and started to be more selective about my subjects. And because I moved in the scientific community, I ended up with science photography and microphotography – that is something I have been doing since 2005. By a fortunate coincidence, I won at that time the third place in an international competition with my very first picture of a dust particle which I picked up in my garden and photographed still on film via a light microscope. That really inspired me to get involved in microphotography more actively.

When creating pictures, you use also a scanning electron microscope. How did you come up with that idea?

It is something that my colleague Petr Juračka from the Faculty of Natural Sciences came up with. He was in our photo club and did a lot of work with the electron microscope. I became quite keen on this method and have not left it since.

How is actually a microphotography from a scanning microscope created?

The first step is preparation of the specimen. For scanning electron microscopy, it must be completely dry, because imaging takes place in vacuum. Water is removed using increasing concentrations of ethanol, up to 100 per cent. Then the specimens are dried in liquid carbon dioxide, which yields a dry specimen with preserved structures. Then I must move it to a conductive pad and since natural surfaces are not suitable for reflecting electrons, I usually apply a thin coat of gold. Then it’s time to start taking the image using the electron microscope, at which point one has to find the right magnification and angle, which can take dozens of minutes. When you manage to find the right image, it must be processed on a computer. First of all, one has to remove everything that should not be there, because for instance under 3,000times magnification – and I do not use any larger magnifications because I need to preserve certain image quality – one can see every tiny mite of dust. This is followed by colouring, which usually takes me two to ten hours. But one Swiss colleague, who has better technical facilities and therefore also more detailed pictures, claims that some colour work took him up to 100 hours. In comparison to him, I am really quite fast!

How many such images have you created, and do you have your favourite subjects in the microworld?

Over the years, I created about 300 microphotographs, which represents quite a lot of time. I am interested in objects I visually like, and the colour work evolves from that. This way, I create in a sense non-existent objects and ‘landscapes’. So far, I found plants most interesting. They have highly varied surfaces, though I must admit that so far, I have done only little work with pollen seeds, which are very pretty. Then there are the insects, which have also highly varied structures, but that it something I know so far little about and I would like to learn more.

What would you like to achieve in microphotography?

I do not have any clear goal. I would rather like to try new methods, methods I so far did not have time to explore, such as confocal microscopy. And then I also want to maintain some general awareness of my work. That is why I send my pictures to international competitions. There is no economic benefit in that. Abroad, there is much more interest in scientific photography and there is also better PR for it, so my pictures are better known abroad than at home. Recently, I was browsing through one American monograph on laboratory imaging and photography, and found that in connection with microphotography, they mentioned my name. That made me really quite happy.

Is there anything you could not take pictures of?

At one point, I did documentary photography and I know it would be very difficult for me to photograph war or natural disasters. One must keep certain distance or objectivity when doing that and I am not sure I could manage that. I am much happier when my subjects do not run away, and I can work with them for some time.

You won many domestic and international awards for photographs. Which one do you treasure the most?

Well, it was not a prize, but I really value the fact that years ago, I was approached by the National Geographic. It was fantastic validation, because it is a journal where only the best of the best photographers publish. Aside from that, my photograph was also published by Science, which is also quite a success. Of the current awards, I was very pleased that at an exhibition of selected photographs from the Science Photographer Awards 2019 in London, my picture made it among top ten. I have now two pictures at an exhibition in Rochester, which will travel around the USA and China, and at the Art in Science competition, which is organised by the Copenhagen University, I won in category Humour in Science with my picture of coloured fly proboscis. All in all, this is quite a lot of good news from abroad. In the Czech Republic, I won quite a number of prizes, including the overall top prize in the Science is Beautiful competition.

So, is science really beautiful, and not only through the photographer’s lens?

I do think it is. It depends on knowing how to look at things. I often place under the microscope things which people find a priori unpleasant or ugly. But even flies, which I do not like in real life, are interesting under the microscope. And when, thanks to various imaging methods, I have the chance to see plants and animals in quite a different way, I think I should use that opportunity and mediate this view to others.

Do you have any other hobbies? Do you for instance paint?

I must admit I am really no good at painting and drawing. I may do a decent job in a computer but not by hand. Among other things, I used to be interested in film and literature, but now I have no more time for it. Unfortunately, I have little time even for my photography....

jat

+ výkřik

I especially treasure the fact that years ago, I was approached by the National Geographic. It was fantastic validation, because it is a journal where only the best of the best photographers publish.